Enterprise Value vs Equity Value: What Is the Difference

.webp)

.webp)

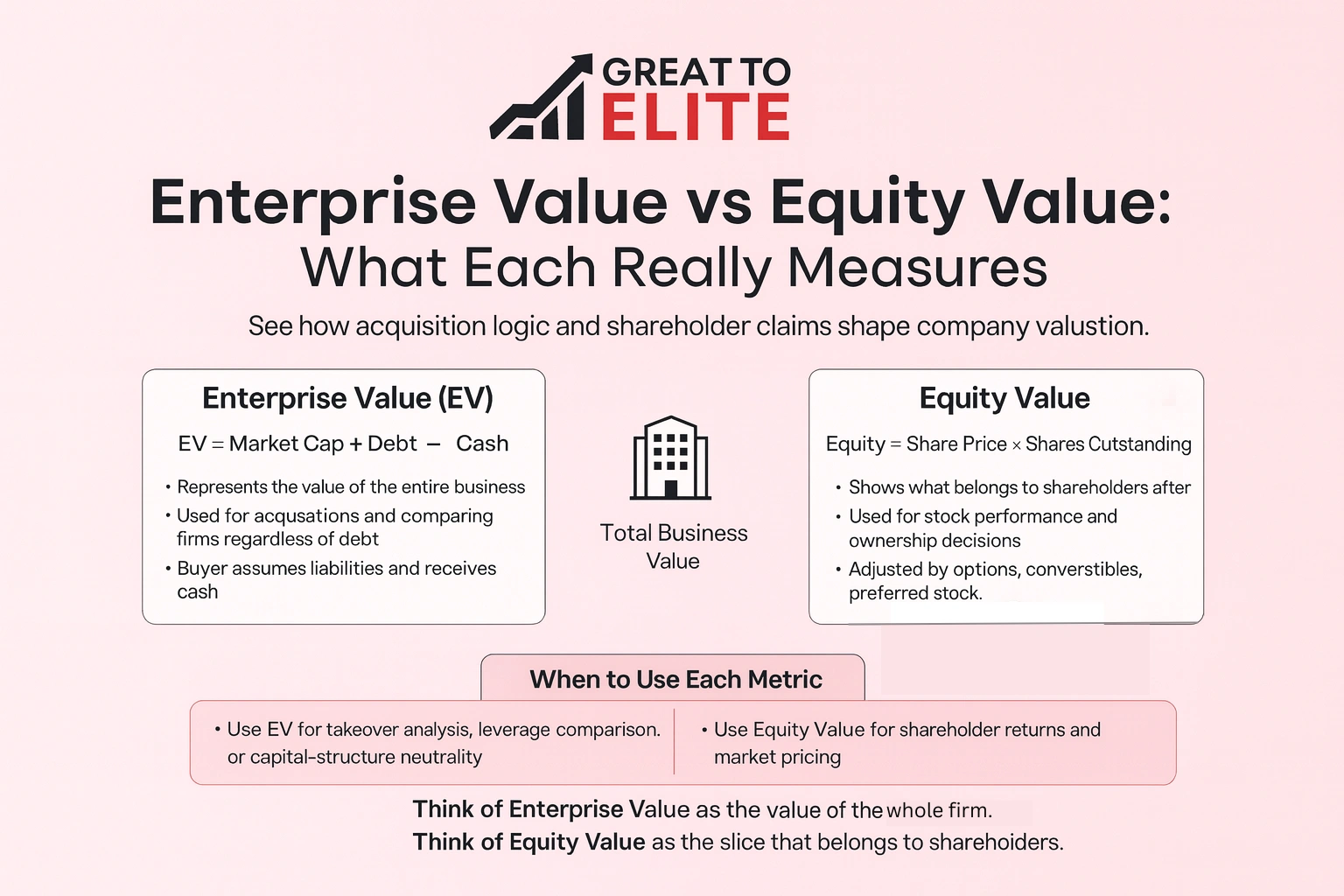

Enterprise value captures the total claim on operating assets, often shown as market capitalization plus total debt minus cash, with minority interests added when present.

Equity value shows what is left for shareholders. You can compute it as enterprise minus debt plus cash, or as the share price times shares outstanding. This is the number most tied to your stock and ownership outcomes.

To make smart comparisons, you must separate the totals that apply to the whole firm from the amounts that belong to shareholders. This section explains each metric and how transaction logic and the balance sheet connect them.

Enterprise value captures what a buyer pays for operating assets. Add market capitalization and total debt, then subtract cash and cash equivalents to calculate enterprise for a takeover.

This measure is neutral to the firm's capital structure because an acquirer assumes liabilities and receives cash. Think of it as the full purchase price before splitting proceeds among capital providers.

Equity value shows what remains for shareholders after liabilities are settled. In public markets, you often see it as share price times shares outstanding.

Adjustments matter: preferred stock, options, and convertibles can change the distribution of proceeds. Use the right metric when you are deciding between buying the whole business or evaluating stock performance.

When analyzing a company's worth, two fundamental metrics often come into play: Enterprise Value (EV) and Equity Value. While both quantify aspects of a company's financial standing, they represent distinct concepts and are used for different purposes.

Equity Value is the simpler of the two, representing the total value of a company's common stock. It is calculated by multiplying the current share price by the total number of outstanding shares. This figure is what public market investors primarily consider, as it reflects the value of the portion of the business they can actually buy or sell.

Equity Value is a straightforward representation of the value of the shareholders' stake in the company. The formula is:

Equity Value = Share Price times Total Outstanding Shares

This metric is most relevant to stock market participants and is the baseline figure used to determine the size of a publicly traded company. It represents the residual claim of the owners on the assets after all liabilities have been settled, and it is the starting point for most valuation analyses. It's an observable market price, meaning it can be directly taken from market data for publicly traded companies.

The "residual claim" aspect: shareholders are the last to be paid if a company is liquidated. Therefore, the Equity Value only captures the value accruing to the owners of the common stock. It is inherently dependent on the capital structure of the company. A company with 1$ billion in assets could have a very high Equity Value if it has little debt, or a much lower Equity Value if it is heavily leveraged, demonstrating that Equity Value doesn't tell the whole story about the company's operating assets.

Enterprise Value, in contrast, represents the total value of a company, encompassing all its sources of capital, namely, the value of both its equity and its net debt. It's the theoretical price a buyer would have to pay to acquire the entire business (the operating assets), including paying off all existing debt and taking control of the company's cash reserves. This metric provides a capital-structure-neutral view of the company's value, meaning it is unaffected by the specific mix of debt and equity used to finance the business. The formula for Enterprise Value is:

Enterprise Value = Equity Value + Total Debt + Preferred Stock + Minority Interest - Cash and Cash Equivalents

The key adjustments made to Equity Value to arrive at Enterprise Value:

EV includes all capital claims and subtracts non-operating cash, and isolates the value of the company's core operating assets (Property, Plant & Equipment, Inventory, etc.). This makes it an ideal metric for comparing competing companies because it removes the distortion caused by differing financing decisions (i.e., high-debt vs. low-debt companies). For example, two companies with identical operating performance but one having significantly more debt will have vastly different Equity Values, but their Enterprise Values should be very similar.

The choice between EV and Equity Value hinges on the purpose of the analysis and the type of financial metric you are calculating.

Enterprise Value is the preferred metric for most sophisticated valuation methodologies, such as comparable company analysis (Comps) and discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis.

Equity Value is primarily used when assessing the value of an individual share or when comparing the size of companies purely from the perspective of their public stock valuation.

Equity Value is the market's perception of the shareholder portion, while Enterprise Value is the comprehensive operating value of the entire business, making it the bedrock for professional financial analysis and corporate transactions.

A small change in funding can shift who keeps what after a deal closes. Capital structure and on‑hand cash sit on the balance sheet and directly affect the bridge between enterprise value and equity value.

Net debt equals interest‑bearing obligations minus cash and equivalents. This shows the true owed amount that an acquirer assumes.

Excess cash reduces the effective purchase price because a buyer inherits that liquidity. By contrast, cash needed for operations is treated carefully when you calculate net cash and working capital.

Minority interests are added to enterprise value because they represent third‑party claims on consolidated subsidiaries' earnings.

Think of the company as a house: the property is the operating assets, the mortgage is debt, and owner equity is the residual after liabilities are paid.

If you borrow and hold the proceeds as cash, the net effect on enterprise value is neutral: an asset and an offsetting obligation net to zero. If you spend that cash on improvements, operating assets rise and the overall price can climb.

Practical valuation hinges on matching your forecast and discount rate to the target outcome you need. In DCF work, projecting free cash to the firm and discounting by WACC gives the whole-company purchase price. Projecting free cash to equity and using the cost of equity produces the per-share figure that shareholders track.

Multiples should map to the level you measure. Use EV/EBITDA or EV/Revenue for whole-business comparisons. Use P/E or price-to-book when you focus on shareholders and per-share earnings. Keeping multiples aligned avoids misleading cross-checks.

Buyers care about normalized operating cash flow, net working capital, and net debt when agreeing on a purchase price. Investors care about per-share earnings, dilution, dividends, and timing of cash flow to holders. Model both paths so you can translate a company purchase price into the equity check at close.

Great to Elite guides companies through valuation and deal readiness with focused, practical workstreams:

Book a call to review your model and map a clear path from operating improvements to the price a buyer will pay and the amount that reaches shareholders.

Pick the metric that matches your aim, pricing the whole firm or tracking per‑share outcomes.

Use the full-company measure when you need a purchase price that reflects all claims on operating assets. Use the shareholder figure when you focus on stock, shares, and what accrues to owners.

Keep modeling consistent: pair FCFF with WACC for the whole-company view and FCFE with the cost of equity for the shareholder view.

Bridge between these numbers with cash, debt, and minority interests so your accounting lines map to the final price and the residual for shareholders.

Apply this framework over time to guide pricing, reporting, and actions that lift cash generation and capital efficiency. Book time with Great to Elite if you want a model review.