What Does Cash Flow Mean When Buying a Business

Cash flow when buying a business means understanding how much liquid cash the company consistently generates after paying its bills, how stable those inflows are, and where pressure points, like slow-paying customers, seasonality, or rising costs, might squeeze your first months of ownership. It’s the financial signal that reveals sustainability, operational discipline, and the true quality of earnings you’re stepping into.

When you buy a company, the timing of available funds can make or break the first months of operation. As cash flow problems are cited as the primary cause in as many as 82% of small-business failures, you must cover payroll, rent, suppliers, taxes, and other obligations exactly when they come due.

Positive cash flow gives you the cushion to handle surprises like repairs or lost contracts. Review billing cycles, deposit rules, and customer payment terms to see whether funds arrive when needed.

Look for timing mismatches: slow payers or long billing lags can leave you liable even if reported income looks strong. Confirm how customers pay, upfront, on delivery, or on net terms, and watch for seasonal dips that affect working capital.

The movement of money reveals operating discipline. Strong invoicing, fast dispute resolution, and tight expense controls show reliable management and healthier financial health.

Action you take: Use these checks to adjust price, require holdbacks, or set lender expectations so your first months of ownership stay on track.

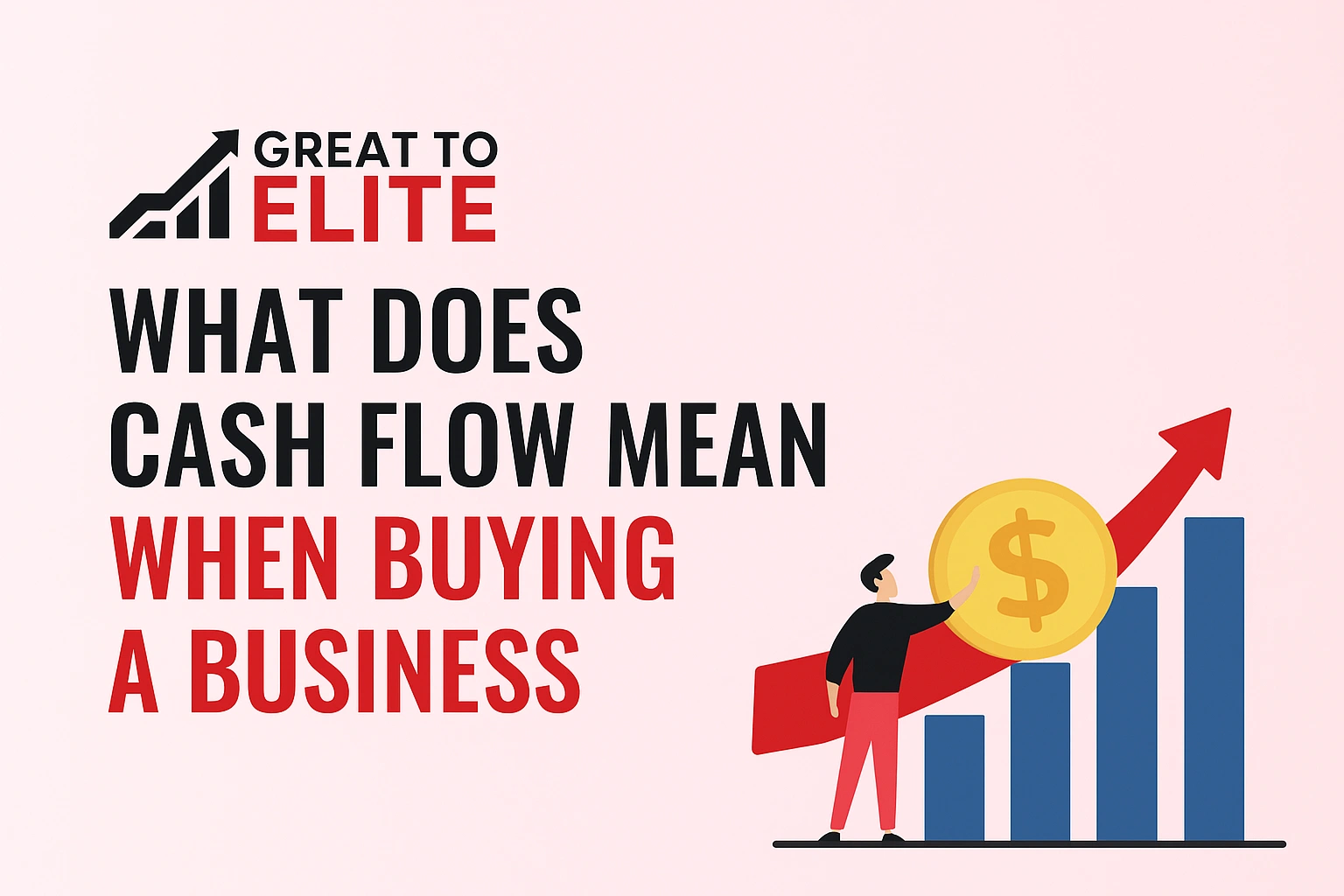

Before you commit, understand how money moves in and out of the company over a defined period. That movement tells you whether the firm generates liquid resources to pay payroll, suppliers, rent, taxes, and other expenses.

Define cash flow as receipts from customers and other sources minus payments for payroll, suppliers, rent, taxes, and operational expenses during the same period. Use the simple formula: net cash = total cash inflow − total cash outflow. This gives a straightforward view of whether the company is producing or consuming funds in real terms.

Positive cash flow shows the business produces more liquid funds than it spends, supplying runway for transition costs, improvements, and debt service. Negative cash flow can be acceptable if tied to planned investments, but you must verify runway and the path back to positive cash.

Treat the cash flow statement as a map that shows where funds came from and where they went during the period. That view helps you separate recurring operating receipts from one‑off investing or financing moves.

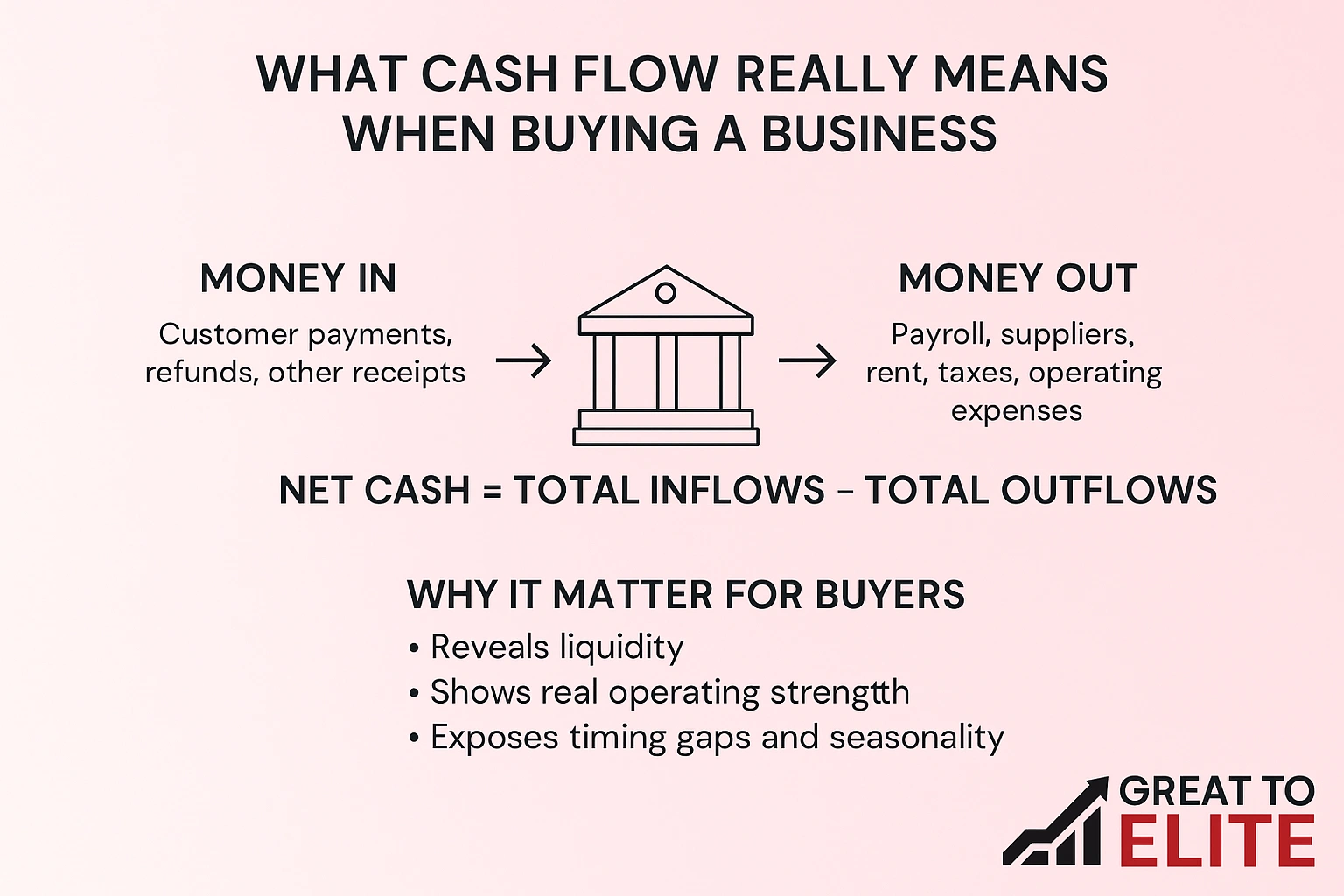

Scan the three sections to see whether operating activity generates most funds or if the company relies on financing or asset sales. Operating entries reflect receipts from customers and payments for expenses and working capital.

Investing rows show purchases or sales of assets and equipment. Negative investing cash may signal healthy reinvestment or an unusual outlay; confirm context.

Financing items reveal debt raises, repayments, equity, and dividends. Heavy reliance on financing can mask weak operating performance.

Validate the arithmetic: net cash = total inflows − total outflows. Reconcile beginning and ending cash for the period to confirm accuracy.

Test whether sales convert to usable funds or whether outside capital fills the gaps. This quick check frames your due diligence and pricing moves.

Examine operating figures first to see if routine operations generate enough cash to cover payroll, rent, and taxes. Adjust for changes in receivables, payables, and inventory to find the true amount available each month.

Review investing entries to spot purchases of equipment and other assets. Negative investing cash may reflect healthy investments, but verify whether those investments are planned growth or catch‑up spending that raises future costs.

Check financing flows for debt draws and repayments, plus owner distributions. Heavy reliance on external debt or frequent dividends can drain funds you will inherit and alter your ability to fund strategic investments.

Separate top‑line sales, accounting profit, and the actual cash that changes hands each month. Confusing these terms can derail valuation and financing decisions during an acquisition.

Revenue records sales earned. Profit shows what remains after expenses and taxes. Cash flow tracks real deposits and withdrawals.

Companies often report profit but show negative cash because receipts lag. Customers may pay on terms, inventory can rise, or prepayments for costs drain balances.

Noncash charges like depreciation widen the gap between income and bank balances. Large investing spends or aggressive growth can also create temporary negative cash despite reported profit.

Align valuation and deal terms to cash reality. Tie holdbacks or earnouts to conversion metrics, not just to accounting profit, so your opening months remain secure.

A practical review of recent cash records reveals whether the firm can fund its near‑term obligations. Gather the last three years of the cash flow statement and monthly flow statement extracts for the most recent 12 months.

Calculate Free Cash Flow to see money left after operating expenses and capital expenditures. Then compute Unlevered Free Cash Flow to evaluate operating performance before interest. Use both figures to size runway and discretionary spend.

Compare the cash flow‑to‑net income ratio to test conversion from profit to usable funds. Compute a current liability coverage ratio (operating cash / current liabilities) to check whether the company can cover near‑term obligations without drawing on credit or new debt.

Trace timing: review customer payment terms, days sales outstanding, and inventory builds that can trap funds. Assess expense trends and changes in working capital for hidden pressure.

Document every finding and use scenarios to inform price, structure, and your post‑close plan for cash management. Benchmark results to peers and test the impact of losing a major customer to measure sensitivity.

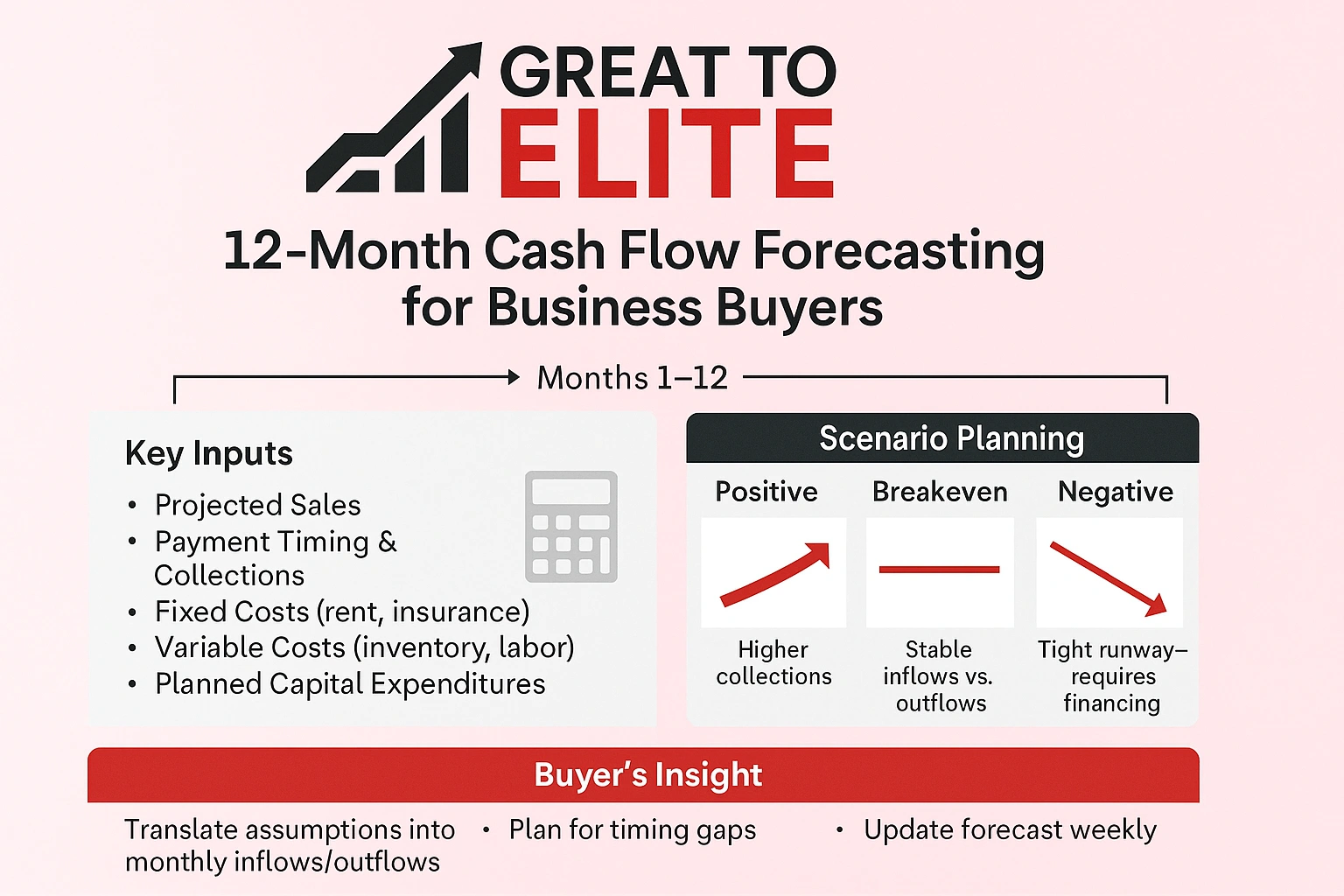

A clear 12-month projection turns assumptions about sales and timing into actionable monthly targets. Use a simple model that converts revenue plans into expected inflows and pairs them with scheduled outflows.

Project monthly sales, then map billing dates and expected collection timing to translate revenue into realistic inflows. Estimate fixed expenses like rent and insurance separately from variable costs such as inventory and hourly labor.

Include planned asset purchases and capital expenditures so investment timing does not stress your liquidity.

Turn the model into an operating habit: update weekly, compare actuals to forecast, and document assumptions so you can refine projections as the company evolves.

Immediate changes to billing and payment timing often free up funds fast. Focus on quick wins you can implement in the first 30 days to protect runway and support operations.

Send accurate invoices the same day work completes. Offer electronic payments and clear early‑pay discounts to shorten days sales outstanding.

Standardize billing steps and automate reminders so no invoice waits for manual handling.

Negotiate net terms and batch payments by due date to preserve positive cash without harming supplier relationships.

Review recurring expenses and costs to trim nonessential spend. Delay planned equipment purchases into cash‑rich months when possible.

Arrange a committed line with clear covenants before you need it. Use financing strategically to smooth timing gaps and avoid expensive emergency debt.

Monitor weekly using a simple statement view so you spot negative cash flow early and take targeted action.

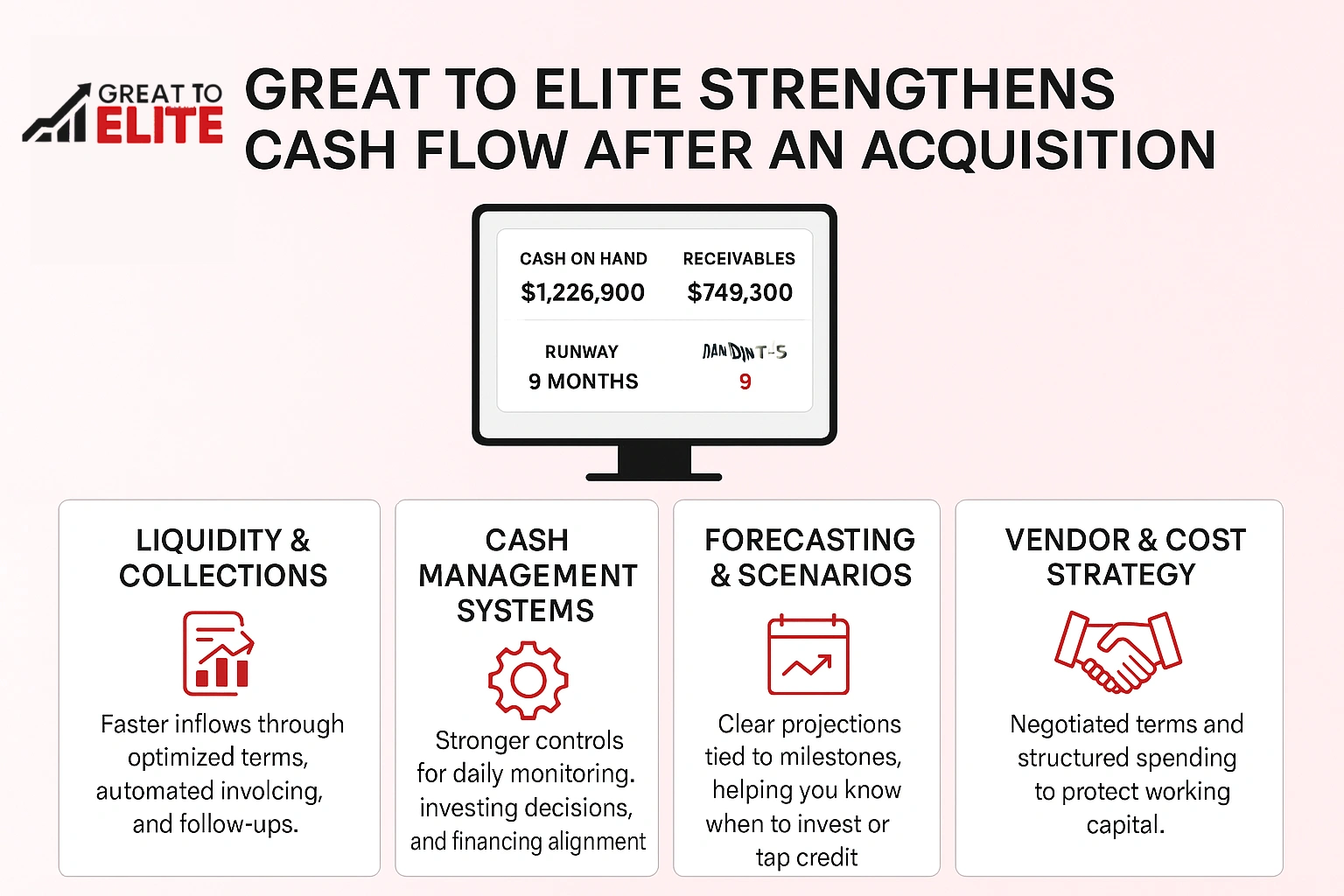

Effective control of receipts and payments gives you confidence in day‑to‑day operations after a deal. Great to Elite partners with you to secure liquidity, tighten collections, and set financing lines only where they add value.

Our approach blends three flow types, forecasting, and practical tools to speed inflows and trim outflows. You keep runway without risking service or quality.

Book a call with Great to Elite to review your target or newly acquired company and get a tailored plan to stabilize and improve liquidity.

The final test is simple: will the company’s net receipts each period keep operations running and growth on track?

Use the cash flow statement with the income and balance statements to judge liquidity, quality of earnings, and working capital needs. Model twelve months to expose seasonality and timing risks so you can act early if balances tighten.

Distinguish profit from usable funds and emphasize operating discipline while aligning investing and financing to sustain healthy net balances. Monitor a few metrics weekly to catch pressure fast.

Engage Great to Elite for structured reviews, projections, and hands‑on implementation so your acquisition decisions protect financial health and obligations from day one.